RIP is a distance vector routing protocol and the simplest routing protocol to start with. We’ll start by paying attention to the distance vector class. What does the name distance vector mean?

- Distance: How far away? In the routing world, we use metrics.

- Vector: Which direction? In the routing world, we care about which interface and the IP address of the next router to send it to.

I don’t know if you ever go cycling but here in The Netherlands, we have some nice so-called mushroom signposts telling you which way to go and how far (in kilometers) the destination is. The same principle applies to distance vector routing protocols.

If you don’t like cycling, you’ll like the highway signs better:

Enough about cycling and highways. Let’s see how distance vector routing protocols operate.

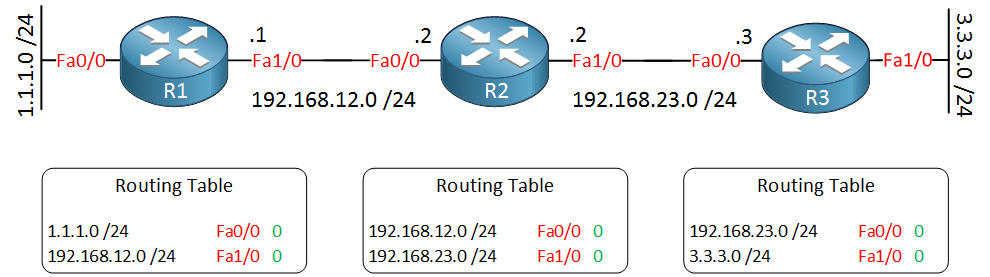

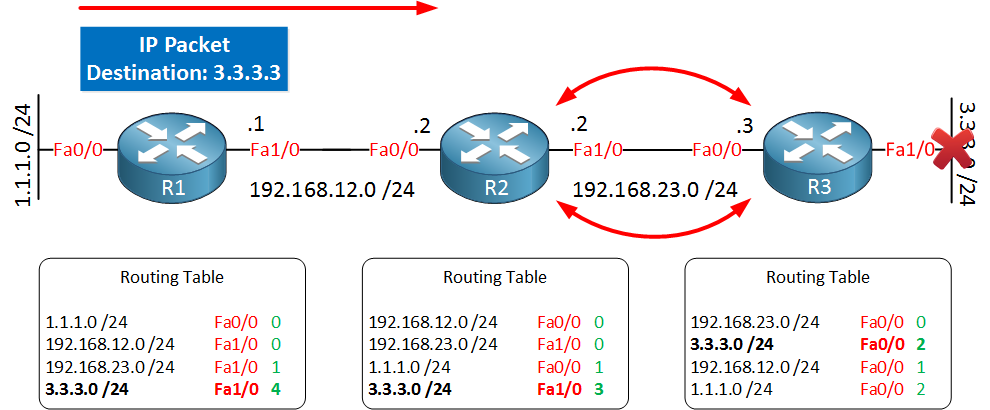

In this picture, we have three routers and we are running a distance vector routing protocol (RIP). As we start our routers they build a routing table by default but the only thing they know is their directly connected interfaces. You can see that this information is in their routing table. In red, you can see which interface, and in green, you can see the metric. RIP uses hop count as its metric which is nothing more than counting the number of routers (hops) you have to pass to get to your destination.

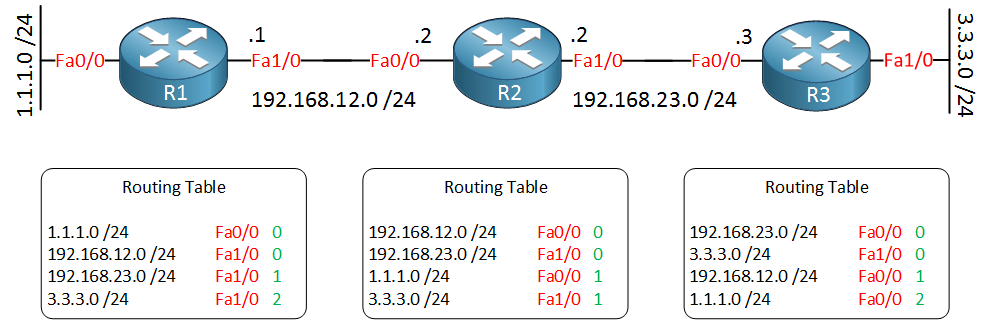

Now I’m going to enable distance vector routing. What will happen is that our routers will copy their routing table to their directly connected neighbor. R1 will copy its routing table to R2. R2 will copy its routing table to R3 and the other way around.

If a router receives information about a network it doesn’t know about yet, it will add this information to its routing table:

Take a look at R1, and you will see that it has learned about the 192.168.23.0 /24 and 3.3.3.0 /24 networks from R2. You see that it has added these two items:

- Interface (Fa1/0. This is the vector part, we know in what direction we have to go.

- Metric (hop count). This is the distance part, we know how far away the network is.

192.168.23.0 /24 is one hop away, and 3.3.3.0 /24 is two hops away.

Awesome! You also see that R2 and R3 have filled their routing tables.

Every 30 seconds our routers will send a full copy of their routing table to their neighbors who can update their own routing table.

So far so good, our routers are working, and we know the destination to all of our networks…distance vector routing protocols are vulnerable to some problems, however. Let me show you what can go wrong:

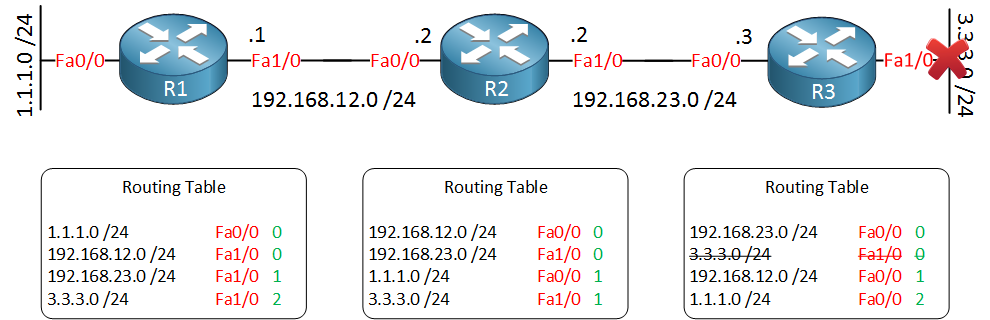

The FastEthernet 1/0 link on R3 is going down, so it will change its routing table. Its status went from 0 to Down.

Every 30 seconds our routers send a full copy of their routing table to their neighbors, and it just happens to be that it’s time for R2 to send a copy. R2 sends his full routing table toward R3. What do you think will happen?

R3 gets the routing table from R2 and will see that R2 is advertising the 3.3.3.0 /24 network with a hop count of 1. That’s excellent is what R3 thinks….a hop count of 1 is better than having a network that is down. R3 will add this information to its routing table.

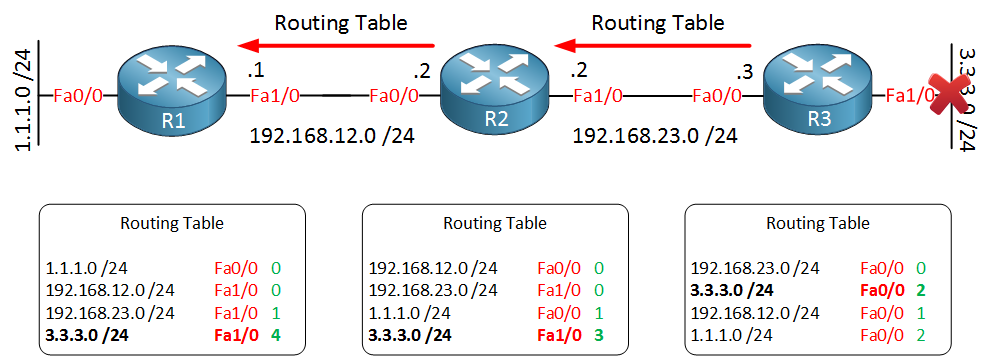

A few seconds later, it’s time for R3 to send its routing table to its neighbor R2. R2 will come to the following conclusion:

“I can reach 3.3.3.0 /24 by going to R3 and my hop count used to be 1. I’m receiving a routing table from R3 now, and it now says that the hop count is 2…I need to update myself to include this change”.

The hop count on R2 is now 3, it received two from R3 and adds the hop towards R3.

R2 will also send a copy of its routing table to R1 which will update itself as well.

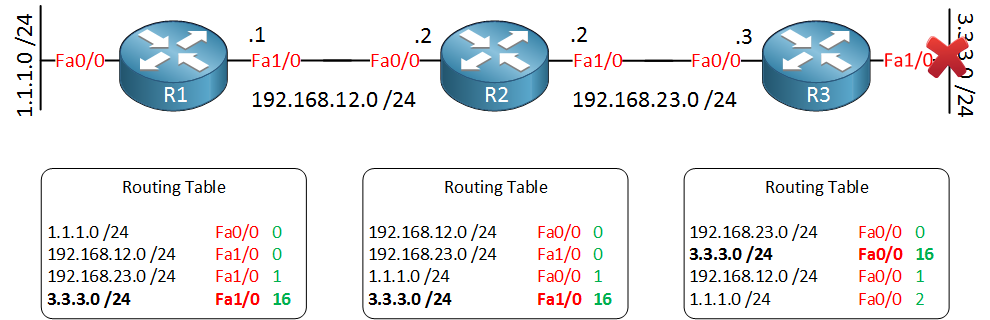

Do you see where this is going? These routers are going to keep updating themselves to infinity.

What will happen when we send an IP packet to the 3.3.3.0 /24 network?

Look at the routing table of R2 and R3. They are pointing to each other. Ladies and Gentleman…we have a routing loop! That’s not a good thing, IP packets have a TTL (Time to Live) field however so they won’t loop around forever as Ethernet Frames do.

To prevent routers from updating themselves over and over again, we have a maximum. For RIP, this is a hop count of 16. 16 is considered unreachable, so the maximum number of hops you can have is 15.

This problem is called counting to infinity.

There is something else we use to counter the counting to infinity problem. In our example, R3 advertised the 3.3.3.0 /24 network to R2. How useful is it that R2 advertises this network to R3?

That’s like telling someone a joke that you just learned from that person…not very effective (unless the joke is extremely good/lame 🙂

In routing, it’s not very effective, so whatever you learn from your neighbor, you will not advertise back to him. We call this split horizon.

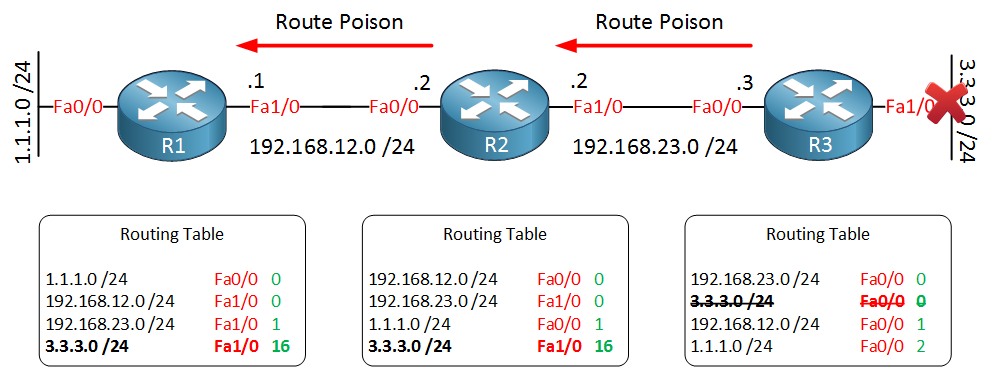

Something else we do is that once a network goes down (3.3.3.0 /24 in our example), the router will send a triggered update immediately to update its neighbors.

The triggered update will contain the network that is down and an infinite metric (16 in the case of RIP). Sending an update for this network with an infinite metric is called route poisoning.

xv

xv

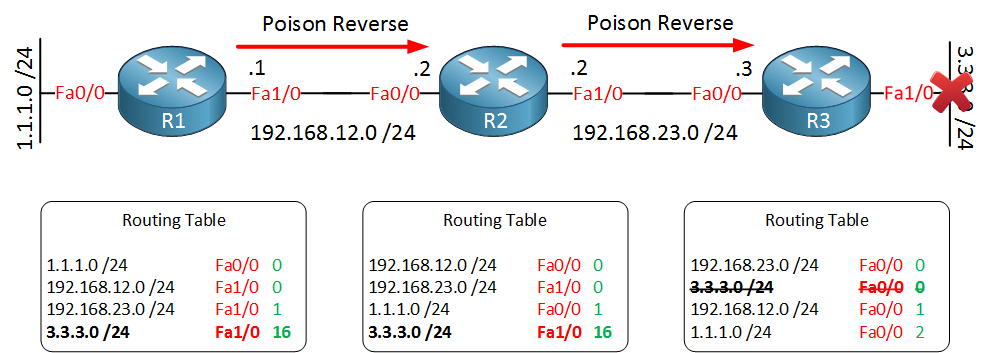

To make sure R3 does not update itself via some other router/path in the network, R2 will send a poison reverse in response to the route poison it received from R3.

I just explained to you what split horizon is…” don’t advertise whatever you learned from your neighbor back to them.”

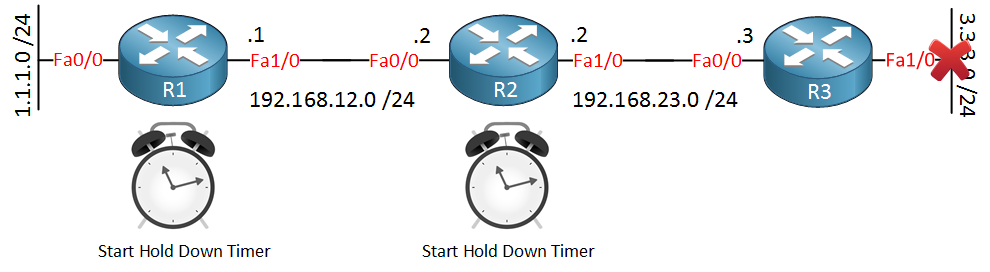

There is one more thing we use with distance vector routing protocols. When R2 and R1 find out that our 3.3.3.0 /24 network is down they will also start a hold-down timer. This hold-down timer will run for 180 seconds and it does the following:

- If we receive information about the 3.3.3.0 /24 network from another router with the same or worse metric than we currently have, we ignore this information.

- If we receive information about the 3.3.3.0 /24 network from another router with a better metric, we stop the hold-down timer and update our routing table with this new information.

- If we don’t receive anything and the hold-down timer elapses we remove this network from the routing table.

What do you think? That’s plenty of information about RIP and distance vector routing protocols, right?

Let me finish this lesson by giving you an overview between RIP version 1 and version 2. They are similar with a few differences:

i have two question

1- split horizon : it’s not useful to advertise network back to the neighbor through interface which came from this neighbor because he is closer to this network than me. the question is what happen when i learned the same network from another neighbor in the following cases 1-with lower metric

or 2-higher metric

or 3- equal metric

2- question two how split horizon works if we have example

1-RI connected to R2 and R3

2-R2 connected to R1and R3

3-R3 connected to R1and R2

It was my first time to read about the RIP, the way the Protocol is explained is very clear and straight forward. Thanks

Rene,

... Continue reading in our forumI’m using the Boson Netsim 9.0 simulator and I configured a lab to match what you laid out in this lesson, what has me baffled is how and where do you see the hop count message of 16, when I shutdown the interface on my R3 router (LAN) 3.3.3.0/24. I turned on debug IP Rip on my R2 router to view the updates being sent from R3. I did see the metric count reach 4 and after that the route was deleted for network 3.3.3.0/24, I never saw the hop count reach 16…just curious about this.

Otherwise a very good explanation and write up RIP protocol

It could be the

Hi Darren,

It might be the Boson simulator, you could try this in GNS3 with two routers…see if the output is different than in Boson.

Rene

Very Very nice explanation, Thanks